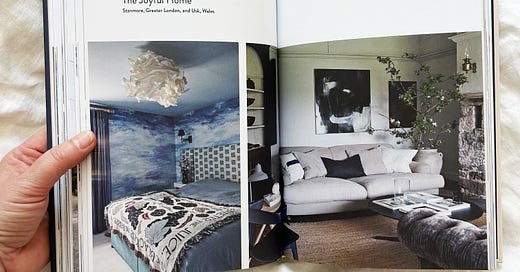

It’s officially publication day for HOME MATTERS!

To celebrate I’m sharing an extract from the book. It’s from a chapter called The Joyful Home where I explore ideas of adornment, pleasure and art at home.

Enjoy!

Usk, Wales

I get up very early one morning and hop in my car, not stopping until I’m over the Welsh border. I have come to see Sonia Pang, curator and owner of Gallery At Home. A former university lecturer in fine art photography, Sonia turned to curating when illness meant she had to take a step back from her work as a lecturer. With her health poor, but itching to get stuck into some work, she set up an exhibition in her own home and it was a roaring success.

I make my way up the drive across a paddock and arrive at the front of the beautiful Welsh longhouse. Sonia and her partner and her youngest child moved in late last year and they are still working on the house. She greets me at the door, and we sit down in the dark, simply furnished living room to have a coffee and a chat.

‘Gallery spaces can be so reverent,’ she tells me. Part of what she is trying to achieve with Gallery At Home – which is actually in a gallery space now and no longer based in her home – is a way for people to connect with art accessibly. To show how art can work in a home setting. Art is for everyone, and it doesn’t always feel that way when it’s viewed in a gallery.

‘I curate my home,’ she says. ‘It’s completely intrinsic to my mental health. I do it on a multi-sensory level. I use art, furniture, music, fragrance. It brings me a huge amount of joy.’ In the room we are sitting in, there is a wall-length shelf running across it, which currently houses a large piece of work by one of her artists, Toril Brancher – a photographic print on aluminium of a large head of cow parsley. Along the shelf is a single stem in a bud vase, a candlestick and some other small objects. I ask her if she changes the display around much and she laughs.

‘It was different this morning and it will be different again tomorrow.’ This is the whole point of the long shelf. It allows her to move her displays around with ease, whenever she gets the itch to do so. Sonia doesn’t just see the kind of work she sells in her own gallery as art. She brings nature from the outdoors in, puts together collections of objects, including ceramics and glass as well as found objects. She displays some of her own work, too. There is a small print of two girls in white Victorian nightgowns – her daughters, now both grown up, when they were young. It was taken with a pinhole camera. It is a piece of art on its own as well as being wrapped in memories for Sonia of the day she took it, of the choice of the nightgowns and the experiments with the homemade camera. Layers of visual cues all in one small white rectangle. It is more than just a photograph.

‘The shelf, for me, is allowing something to be temporary, fluid and changeable. It can be fresh and seasonal. It can house objects, ceramics, photographs, paintings. Anything. It’s all artwork. Their value is dictated by the gaze of the viewer.’

Upstairs in her calm and sparsely furnished bedroom, Sonia shows me a display on her chest of drawers. It has personal objects on it that are deeply meaningful to her, many of them given to her by her daughters. When does a simple object become art? It’s all about context, value and display, she tells me. When very personal objects are curated and brought together in a way that takes their visual elements as well as their meaning into account, they become art. ‘I’ve curated things so that they are visually appealing to anyone, but for me they have layers of meaning and memory, too. To me, they are emotive. They keep me connected to my family, to people I love.’

When it comes to the art we buy, Sonia tells me, one of the problems is that we start worrying about things like value. Are we making a good investment? She doesn’t think that’s the question you need to be asking yourself when it comes to art.

She tells me the story of when she was married to her first husband and her daughters were very young. They had just bought a house and they had no money, but they had the opportunity to buy an Ernest Zobole painting, which was £495. They raided their overdraft to buy it and brought it back to their new home. They didn’t even own a bed at the time. She said maybe that was crazy, not to buy a bed but to buy a painting instead. Zobole has since died and the painting, which is upstairs in Sonia’s office, is now worth about £5,000. ‘Would I ever sell it? No way! I remember the night we bought it. I remember the joy of hanging it in our home. The value is in the painting itself and the memories, not the monetary value. That painting is thirty years old and I still look at it and get joy from it.’ So what does it matter that it was technically a ‘good investment’ if Sonia has no intention of selling it? It doesn’t matter at all.

‘Art is essential. It’s as fundamental as music and food and all the other cultural things we seek out to make life richer. What’s the point otherwise?’ she says.

I find this an interesting thing to point out. There are lots of things we do as humans that might be deemed unnecessary for survival. We could eat very basic, well-balanced diets with no fuss or frills or flavour if we were only eating to survive. We could communicate everything through facts rather than fiction. We could speak instead of sing. We could live in warm and dry but completely unadorned homes. But we don’t.

‘The artwork we have in our homes, it’s the colour we bring into our lives. Otherwise, we’re just living in a box. Even if we were stuck in a cell, we’d probably scratch some markings onto the wall.’

Sonia tells me about the book The Thoughtful Dresser by Linda Grant, in which she explores why clothing and adornments are so important to us. In it is the story of a couture seamstress in a concentration camp who customised her fellow inmates’ prison uniforms and made headdresses and hats out of scraps of material. It reminds me of another Second World War story of a group of young Girl Guides interned in Changi Prison in Singapore after the invasion, who decided to sew a beautiful quilt for their Girl Guiding leader as a gift. They used pieces of fabric torn from clothes and uniforms, creating a rosette pattern. The centre of each rosette has a name embroidered into it. It’s incredibly beautiful. The piece now hangs in the Imperial War Museum in London. We turn to art, even in the most horrific of times. Perhaps it is then that we need it more than ever, to remind us of what there is to live for.

In Sonia’s calm, light bedroom, she has a very small Sam Lock painting, in gold, taupe and cream tones. It sits on an otherwise vast and empty wall, to the right of her bed, rather than centrally. It is counter to what many would think of as the ‘right’ way to hang a piece of art. But it has created the exact feel Sonia wanted. It is tranquil and reflects the feeling of serenity she wanted in the room, with all that negative space.

On the chest of drawers, among the items her daughters have given her over the years, sits a small, square black and white photo. The surround of the photo is white, and at the bottom a large nappy pin has been stuck though it. The photo is of a baby girl, lying on a blanket, the shadow of a woman across her. The baby is Sonia. Her birth mother, who had her adopted at three months, took that photo just before she said goodbye to her. The day she gave Sonia away, she removed the pin from her nappy to keep with her. When they met for the first time when Sonia was thirty, her birth mother gave her the nappy pin, along with the negatives for the photo – a tangible reminder that her birth mother had not wanted to forget. Sonia printed the photo herself and placed the pin in the bottom. It sits alongside the other objects that connect her to her family. A simple display that represents the past, the present and the future. I think it might be the most beautiful piece of art in the whole house.

On my return from Wales, I attend to a job I have been meaning to do for years. Among the items I kept of Mum’s belongings is a large watercolour painting of irises – my mum’s favourite flowers. She bought the painting while we were visiting my dad when he was working in the US. I remember it in every house we lived in. It is present in the background of countless birthday celebration and Christmas photos. It has been unframed and shoved beside my wardrobe for years. I pull it out and take it to the picture framer. A few weeks later, it is up in my bedroom. Looking at it, I feel so connected to my mum that I now understand why I put it off for so long. It’s large, beautiful presence is as much her as a photo of her would be. Perhaps even more so. I think of how my daughter will, over time, begin to associate it with me. My past and my future converging in a way that feels rare. My mother died long before my children were born. There is an unfathomable chasm between them that is hard to bridge. Perhaps it is objects like these that can help to bridge that gap.

Our desire for beauty is perhaps our desire for connection above all else. Connection to our pasts and to those we love. Our need to adorn our homes, to make them more than just a box or shelter, is perhaps connected to our desire to live beyond the immediate moment. We can be reminded that we are not alone, that we have ancestors and pasts, and we have futures, too. And they are all interconnected.

Home Matters is out now

The book i never knew i needed! thank you!

A beautiful extract! 🩵 Thank you for sharing.